Emily Mito ’28

Staff Writer

Throughout history, balloons, pigeons, airplanes, and later drones have been equipped with cameras for aerial photography.

Since the first aerial image was taken in the late nineteenth century, human society has become obsessed with the “non-human eye” in the sky.

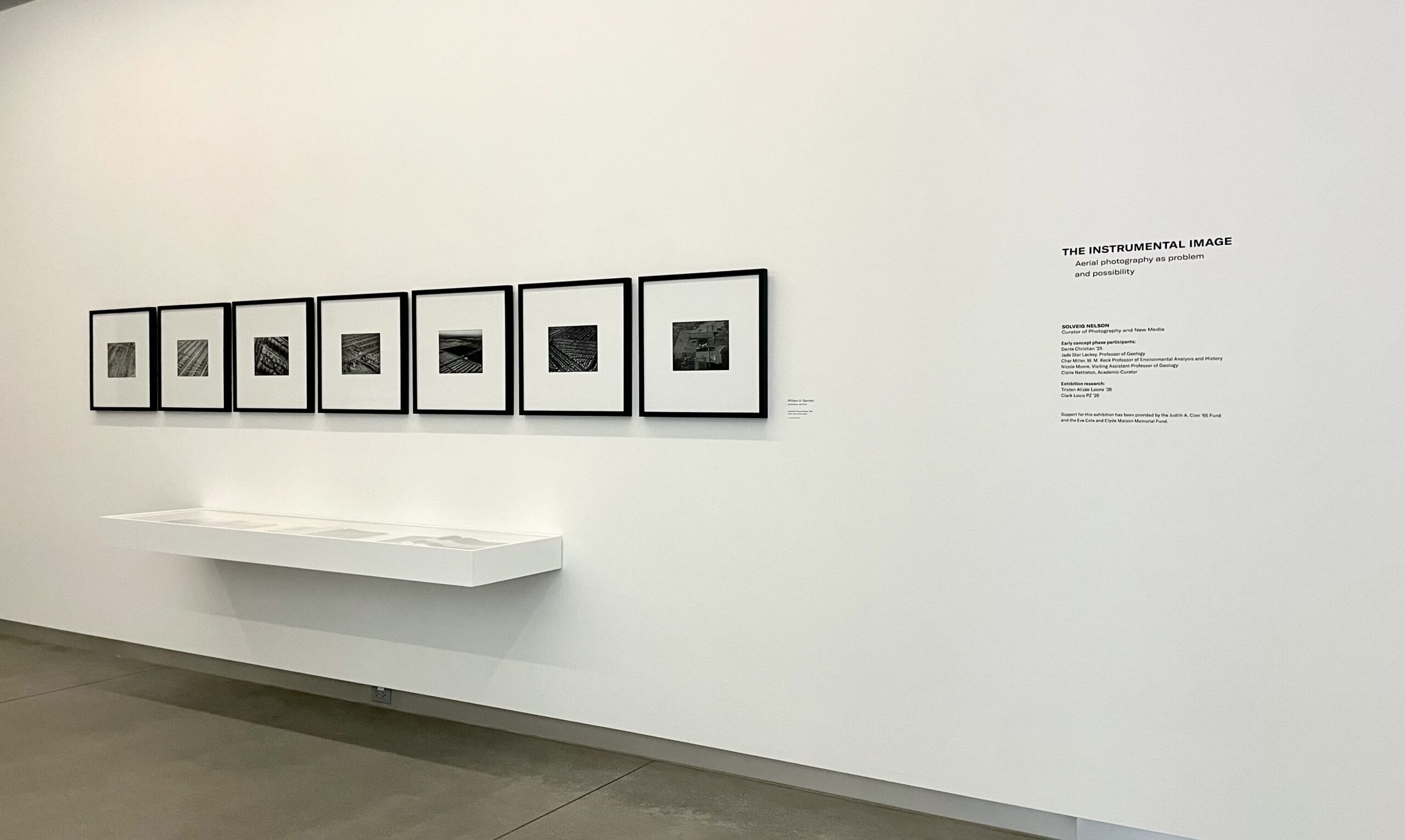

The Instrumental Image—Aerial Photography as Problem and Possibility is on view at the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College from Aug. 15 to Jan. 5.

The exhibition explored different problems and possibilities of aerial photography.

Solveig Nelson, the museum’s newly admitted curator, started working on the exhibition over the summer prior to her arrival in Claremont.

When grappling with the abundant photo collections of the Benton Museum, Nelson first encountered the wartime images, which are essential to the history of aerial photography.

The exhibition is named after Allan Sekula’s landmark essay, in which the author criticized the use of aerial photography during World War I as a tool to aestheticize violence and thus minimize the human cost of aerial attacks.

The first image of the exhibition, a photograph taken from the airplane of Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio in 1919, shows a city rained with thousands of propaganda newspapers. Nelson said in an interview with The Scripps Voice that the image invites viewers to “the contemplation of aerial view as an abstract object and dissonance with an inability to see the violence.”

By looking down at the cityscape in a museum exhibition, visitors inevitably put themselves in a certain hierarchical relationship to the lives below.

The show continued to explore the aerial images of the Second World War.

Looking at the images like the Reconnaissance picture of the Nazi airfield and the total area devastated by the atomic bomb strike on Hiroshima, Nelson said that: “On the appearance, it is an abstract landscape, but then if you interpret why it was taken and what those little dots are, you realize that there is an inner layer of tragedy.”

The use of aerial photography as a mode of surveillance was persistent during the 1960s, especially to document marginalized African American communities.

In Civil Rights demonstrators march through Springfield, Massachusetts, the aerial perspective seems to distance the viewer from the scene before them. The angle that looks down on the crowd of human figures creates a significant power dynamic between the protesters, the photographer, and, by extension, the viewer.

On the other hand, the exhibition also casts light on artists who practiced alternative ways of using aerial photography.

Roy DeCarava captured intimate scenes of Harlem from above in the 1950s. Instead of applying the orthodox aerial photography styles that show people as a minimized collective, DeCarava’s works focuses on individual narratives as the subjects. The individuals “hold emotional weight,” according to Nelson.

LaToya Ruby Frazier even extends the possibility of aerial photography being used not to undermine but to empower the subject. In 2013, Frazier photographed African American communities in Memphis, Baltimore, and Chicago. In an interview with The Atlantic, Frazier explained how she used aerial perspective to help people in the communities see what surrounds them physically and historically.

Aerial photography also plays a significant role in the conversation of environmental justice.

William Garnett’s Lakewood Housing Project, 1950, is especially intriguing as it shows two conflicting intentions around suburban development.

The seven aerial photos showing the process of housing construction were taken by Garnett as part of a commission project. The developers turned them into portfolios to showcase their achievements.

To some people, the geometric patterns of thousands of identical houses lined up perfectly appear to be aesthetically pleasing. To others, the extreme artificiality seems odd and disturbing.

Contrary to the developers’ intention, Garnett tried to show the disastrous environmental impacts of artificial development.

“This series of images shows how construction is paired with destruction,” Nelson said. “They make us wonder what was there before they bulldozed everything to start the construction.”

By showing diverse uses of aerial photography throughout its history, The Instrumental Image—Aerial Photography as Problem and Possibility challenges our most fundamental view of aerial photography as a non-human eye. Although the images are physically taken by non-human media and from a super-human perspective in the air, a human gaze always controls the lens.

Sometimes, the gaze is colonial, suppressive, and egoistic, but other times, it can be revealing and empowering.

Social media and news coverage constantly expose people to aerial images, and if not literal images, the concept of looking down on the world from above. The images can be used for different purposes, such as providing a broader context of an incident or objectifying the human figures on the ground and distancing them from the viewers.

The exhibition encourages visitors to be critical of unconsciously consuming aerial images and intentional about internalized aerial sight. Make sure to visit while it’s still here this semester!

Photo Courtesy: Emily Mito ’28