By Anna Mitchell ’22

I

I know nothing of the desert. I was born and raised in an arctic cave, what Plato imagined to exist in my conscious mind. Plato clings on my neck. An imp. One hair, two hairs, blown out of his scalp. They drifted, like samaras, down the slopes of my shoulder – and hip and calf and heel – onto the gravel of our driveway. Summers were sticky, even at the end of the earth, so we guzzled powdered lemonade and sweat through our jackets. I know shades of grass, the wet undersides of boulders, radio hum, and steamy venison stew.

My house, or, what later felt like an envelope, a porcelain tub, a cranny between glaciers. An inky airway between two frigid palms. A painting restored by the not-so-nimble hand of recollection.

Despite our utter lack of each other, the desert seems to know lots about me. Before we even met. So, finally, we meet. And it floors me, how intricately and intimately I am known by a sand dune. Why does this surprise me? How undeveloped must I be? Minerva Hoyt would have punched me.

II

Here is a brief account of why I am here:

One Tuesday, after dropping my apron in the canvas bag, soiled, I was hit with a memory hard enough to bruise the soul like a punch does the body. My father, my sister and I, in search of the big-horned sheep. We wound up wooded hills, down barren gulches; through teeming valleys, over mountains whose slopes appeared gentle as a giant’s knees until you’re see-sawing on its peak.

On our fourth day in transit, still a day’s journey from the sheeplands or holylands or holy sheep lands, out my window, I observed, for the very first time, big love.

The big love was contained by a valley, which we cut through [about where its rib might be] parallel to the low lying creek-spine, iridescent, azur. It was fuller than an unopened ice cream tub, brighter than a day-time television show, vaster than school, deeper than poems can be pressed into stone.

I have yet to see an apron since. That past, I’ve come to understand, is neither within nor without me. It is both.

The vague memory of violet mountains, so compelling as to swell the organ of my brain and induce gnawing, snapping aches. This is why I drink Coca Cola. In a can.

III

I reach the valley in a matter of hours. Father drove roundabout routes, guided by coffee stains on the map. Since retiring myself to the dust, I have become a query-sponge. What can my lover do for humanity? My lover is not a scientist, nor an artist who sharpens his pen on the whetstone of truth. My lover is kind, though he is not good.

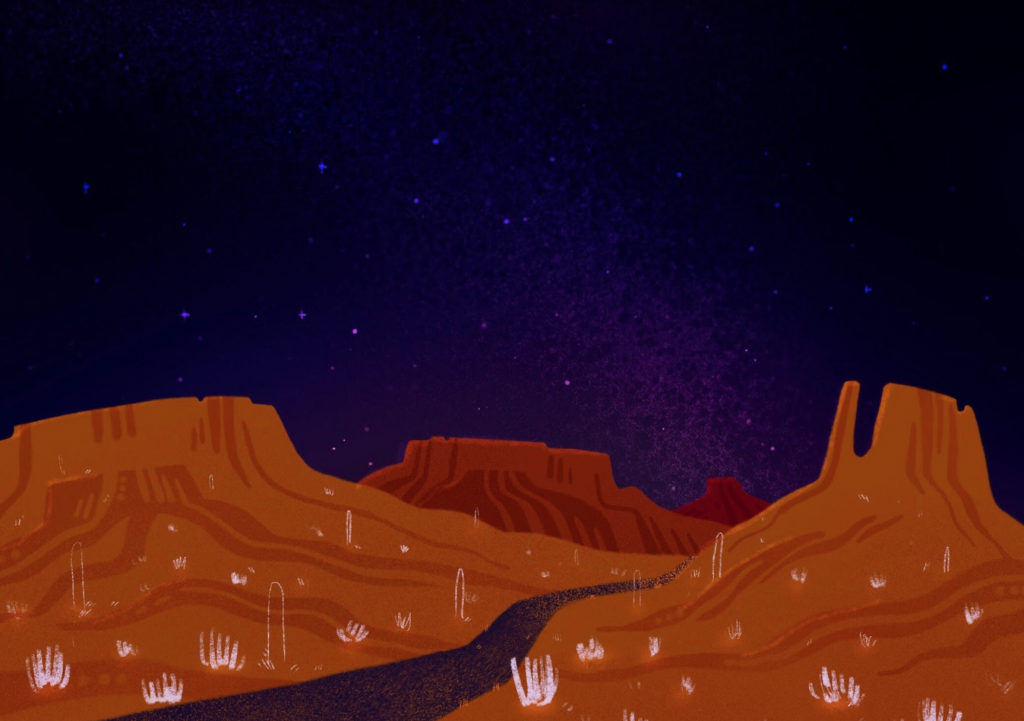

Later, as I pull over towards a plain where one tall plant is silhouetted by the moonlight in the shape of a human, I ponder how like my cave desert at dusk can be. If we work together. Then, nightness smothers day, an impassioned struggle notwithstanding. [The struggle is beauty and power.]

IV

Sand stings sharper than muddy ice crystals, under the crescents of my fingernails, buffed by fatigue and dusty as moth’s wings ablaze under summer lamplight.

V

Without you, the desert is as blank as death. I imagine death both as absence and as waiting. For reincarnation, that is. When I kneel down beside a lone sage, sometimes I think I can almost see the softness of Antonia’s skin in its leaves, the unrelenting summer of her eyes. Oh, Antonia.

VI

At day break, I unfurl, zip on a jacket, twist the hair on my ankles. I adjust my tent stakes, pee, gather debris to light on fire. I stretch out my toes. They do the writing for me. They write:

To my lover,

You sought quite a different sort of mountain from the one I affix to my internal horizon line. You guzzle thick warm beer like a boar or a bear tantalized by a day in a human’s flesh. You pack cookies with peanut butter and chocolate in all your pockets, in case the snow threatens to swallow you. You trip on small pebbles caught in frozen puddles in the parking lot of a motel, where a bus sputters and squeals, stopping, every morning, at your doorstep. You gather snow from out your sliding glass door and let it melt by the heater, because the very prospect of buying water with such an abundance is like the suggestion that a deer in a lush wood buy a ten foot by ten foot plot of ferns and underbrush for grazing. Or maybe it’s not quite like that. I have never been a deer, and I have not yet stopped loving you, either. I wonder if I will.

Yours,

Cressi

[You are right. This was in no manner intended for matters of the heart. Though I find them now quite inseparable, especially considering that I left him the day I came to the valley. That is not a crucial detail. We are dying, and I must speak.]

Part VII

There is a rule of seven. It is not well known, except for in the desert, particularly in the subterranean jungles such as these that survive as echoes and as shouts. It states that one should pursue no more than seven endeavors at once. You were my eighth. But now, you are the desert. And I ask you, do not repel me, as you do water.

Graphic: Molly Antell Scripps ’19