By Anna Liss-Roy ’20 and Priya Canzius ’20

Editors-in-Chief

Sept. 26, Vol. XXIX, Issue 1

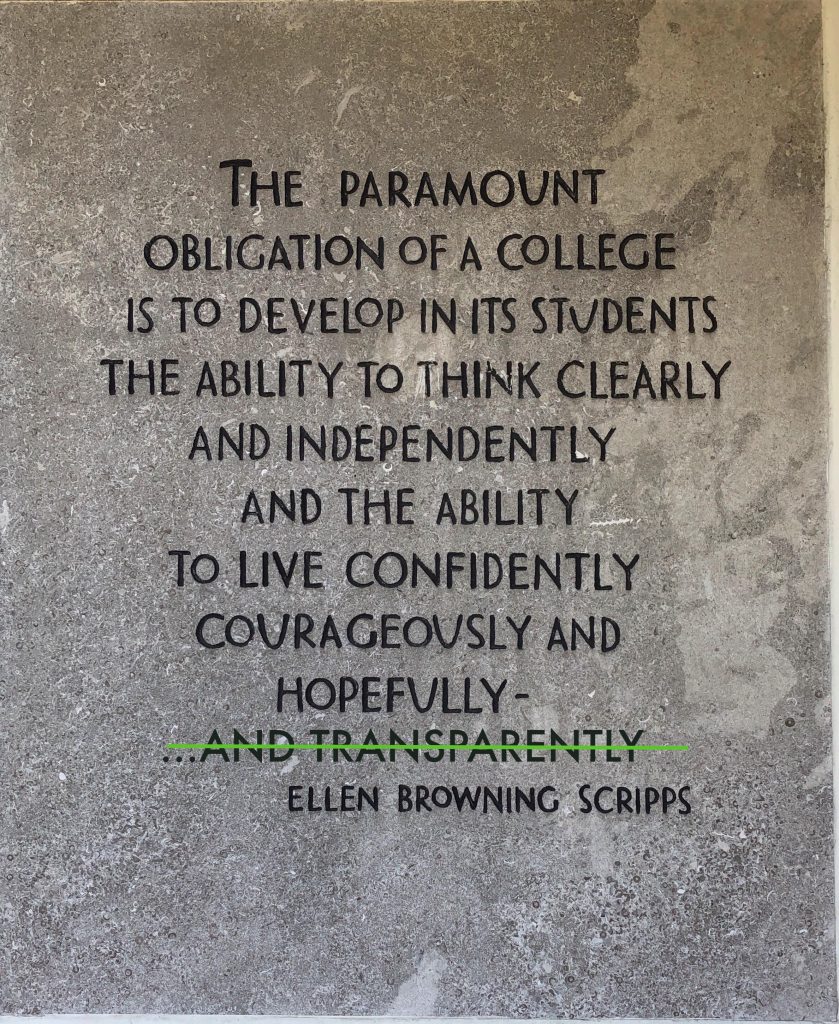

In our reporting, The Scripps Voice aims to continue Ellen Browning Scripps’ legacy of living “confidently, courageously, and hopefully,” as is engraved on Honnold Gate, the official entrance into Scripps College.

Perhaps “transparently” should have been explicitly included in Scripps’ statement.

According to the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics, it is a journalist’s job to seek primary sources for their stories and to avoid undercover or other surreptitious methods of gathering information. Scripps Marketing and Communications, however, is obstructing the ability of publications to adhere to these duties through a procedure that attempts to prohibit direct contact between reporters and Scripps faculty and staff, characterizing itself as a mandated intermediary through which questions and responses must be sent.

This procedure was implemented in 2016, according to Scripps’ Office of Marketing and Communications. However, TSV was first notified of its existence in the fall of 2018. Furthermore, numerous faculty and staff have reported that they were unaware of it until this week.

“We met with Carolyn Robles [Executive Director of Marketing and Communications] and the rest of the MarComm team around the last week of September last year,” former TSV Editor-in-Chief Maureen Cowhey ’19 said. “There is no written document of the policy and we went over it only in person at the meeting. We said that we understood that it was difficult to get inquiries in on time and that we appreciated that they were reaching out to a bunch of people in order to get accurate info but that interviewing people was a crucial part of what we do as a newspaper and that we couldn’t write stories and get the full story without that face to face interview interaction.”

The Marketing and Communications team has also stated that reporters may be able to hold in-person interviews with faculty and staff members, but that these interviews may only occur if the meeting is set up by Marketing and Communications, and only if the team receives the reporters’ questions in advance.

Over the course of the past three weeks, including during a workshop designed to cover Scripps’ media “policies,” as stated in an email by News and Communications Strategic Specialist Rachael Warecki on Sept. 4, adherence to this procedure was communicated to be mandatory.

On Sept. 25, several days after the Office of Marketing and Communications was informed that TSV was publishing an article on the procedure, the language used to describe the procedure by Marketing and Communications appeared to be more relaxed. TSV held a meeting with Assistant Dean of Students Adriana di Bartolo and Warecki, during which di Bartolo and Warecki stated that the procedure communicates a “strong ask,” but not a requirement, because reporters have the ability to violate the procedure. They denied that this description was a departure from the way it had been previously communicated.

The way this procedure has been disclosed to on- and off-campus publications is a form of censorship and is raising concerns among faculty and staff. It is even considered illegal, according to a center focused on the law of gathering and disseminating news across all platforms and technologies.

“The danger is that journalists receive filtered comments and won’t be sure if they are getting the complete story,” said CMC Journalism instructor Terril Jones, who has formerly worked as a reporter and editor at Thomson Reuters, the Los Angeles Times, Forbes Magazine and the Associated Press. “While the intention of such a policy may be positive, such as to streamline the comment process or eliminate conjecture, it also raises questions about the narrative and facts if quotes go through vetting first.”

According to Jones, news consumers who read that a statement was provided by a firm’s public affairs department may become skeptical of the newspapers’ integrity.

Robles explained the reasoning behind the procedure in an email to TSV on Sept. 21.

“The Office of Marketing and Communications is responsible for managing media relations on behalf of the College, which includes responding to reporter requests, ensuring that the College provides accurate and timely information to the media, and maintaining records of media inquiries,” Robles said.

According to Robles, the procedure includes “asking that all journalists, without exception, provide their questions in writing [to the Office of Marketing and Communications] … ensuring that the College provides accurate and timely information to the media, and maintaining records of media inquiries … and that the reporter’s ability to obtain responses within the short deadlines that accompany most media inquiries is enhanced.”

Jones is familiar with procedures such as this one.

“If carried out in a timely way, such policies can be helpful to all parties when reporters are seeking official, institutional comment about an issue,” said Jones. “What’s of concern is to have a third party such as a public affairs office or a PR company handle quotes and information reporters are seeking from primary sources.”

Jones also questioned the ability of such a procedure to increase efficiency and build trust.

“It raises questions of transparency and motive, and also slows down the newsgathering process, which can be a problem on deadline,” he said.

In an informal poll sent to Scripps faculty and staff by TSV on Sept. 23, 73.7 percent of respondents said that they either had not or could not recall being notified of this procedure and 89.5 percent said they do not approve of this procedure. 81.3 percent said they will not adhere to the procedure.

On Sept. 24, Robles sent an email to faculty and staff addressing the poll and sharing the full statement she had provided to TSV. In this email, Robles took issue with TSV’s description of the policy as “recent,” stating, “this is not a new policy, rather an ongoing practice that has been in place for at least four years.” However, this contradicts Robles’ previous statement that the procedure was implemented in 2016. Moreover, Robles did not dispute TSV’s statement to faculty/staff that it was communicated to be a mandatory procedure.

From the poll and email interviews, TSV has gathered information which suggests that faculty and staff were largely unaware of this procedure before the poll was shared by TSV and that they overwhelmingly feel negatively toward it. Below are several faculty and staff statements about the procedure:

“I don’t recall receiving any information about a revised communications policy,” Thomas Kim, associate professor of Politics, said in an email conducted independently of Marketing and Communications. “It’s hard to imagine faculty actually following this policy. They might be completely unaware of it, or they might simply choose to ignore it.”

“As I know, the faculty have not been notified of this policy,” said Kim Drake, Chair of the Writing Department, in an email interview also conducted independently of Marketing and Communications. “From what I understand, it is trying to control student journalism and faculty contact with student journalists, which seems highly problematic, if not a violation of First Amendment rights.”

“Clearly, I won’t have reporters submit written questions to the PR office instead of interviewing me directly,” said Rivka Weinberg, professor of Philosophy, in a response submitted through the poll. “What jurisdiction does the PR office have over faculty interviews with journalists or anyone else?”

“Neither questions nor responses should have to go through MarComm (Marketing and Communications). I will not submit my responses to MarComm,” said Rita Cano Alcalá, Associate Professor Hispanic Studies and Chicana/o – Latina/o Studies, in a response submitted through the poll. “It constitutes censorship. I question the legality of this policy I’d never heard of before. I challenge the ethics of it. It feels like Big Brother.”

Out of some 30 opinions solicited for this story, only one respondent said they recalled the procedure being mentioned at a Scripps faculty meeting two years ago. This anonymous respondent stated that they “believe there are benefits [to the procedure, as]…MarComm has correctly identified me as an appropriate responder to some requests I would not otherwise have received.”

In addition to ethical concerns, this procedure could have negative repercussions for faculty members whose contact with news media is often time sensitive. “I’ve worked for many years with people who have no affiliation to Scripps College. They would’ve quit working with me if I told them that rather than responding to media requests, that I would refer media to a college intermediary,” Kim said. “If you’re not available to respond right away, news media moves on quickly to the next available person. It’s inevitable that you will lose opportunities to speak to the media under this policy.”

Some faculty and staff members anonymously expressed hostility toward the procedure.

“It’s the most unusual and far-reaching policy in terms of PR I’ve ever heard of,” said one respondent. Other anonymous responses included, “I’ll probably stop responding to reporters,” “The quality of PR related releases will likely decrease by adding an intermediary who is not an expert in the field,” and “I would never adhere to this policy.”

Several faculty and staff members responding to the poll voiced suspicion about the execution of the procedure.

“It would make me less likely to answer questions from anybody as I would assume that the Marketing and Communications would be keeping a list of ‘friendly’ faculty and that that information might be used against ‘unfriendly’ faculty in hiring, promotion, and salary decisions. I would boycott on principle,” another respondent said. “We should be free to ignore journalists without part of our College implicitly demanding that we deal with them. We also would have no knowledge of whether Marketing and Communications was censoring our responses to journalists’ questions. If I said something ‘controversial’ that Marketing and Communications is afraid might hurt the reputation of the College, would they pass it along to the journalist in question? I doubt it.”

Moreover, Rachael Huang, adjunct professor in Music, questioned the reasoning behind the implementation of this procedure.

“At first glance, it looks both unethical and cumbersome,” Huang said, through the TSV poll. “The question is: what is MarComm doing with the responses, such that they cannot go directly to the reporter?”

No other 5C Marketing and Communications office uses comparable language to discourage direct faculty/staff-media contact. Like Scripps, neither Pitzer nor Harvey Mudd has a written procedure and both colleges request that reporters notify their respective Marketing and Communications offices when directly contacting faculty and staff, according to Anna L. Change, senior director of Communications & Media Relations at Pitzer College and Judy Augsburger, director of Public Relations and Communications and Marketing at Harvey Mudd College.

However, their procedures do allow for this direct contact to occur.

CMC’s Office of Public Affairs and Communications did not respond to two requests for comment.

Pomona’s procedure most closely resembles that of Scripps but does not restrict reporters from contacting faculty directly, making Scripps’ media procedure appear the strictest at the 5Cs.

“When working with Pomona, if there is a story or a question that [a student publication] has that is strictly pertaining to a faculty members’ expertise, by all means reach out to them directly,” said Patricia Vest, Pomona’s Associate Director of News and Strategic Content. “If it’s a question or story more on the institution side … then we recommend coming through us. We will find you [an appropriate interviewee] in a timely manner.”

TSV has not yet contacted faculty or staff from the other Claremont Colleges about their opinions on their respective campus’ policies.

As Scripps faculty and staff concerns continue to rise, broader legal concerns have also emerged. On Aug. 20, The Scripps Voice was contacted by Frank LoMonte, director of The Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida, who had flagged the Scripps media policy as a “‘gag’ policy” and found it worthy of investigation.

LoMonte expressed concern about the procedure’s legality in an email on Sept. 23.

“Because Scripps College is a private institution, the standards for employees’ rights are set by the National Labor Relations Act, which applies to private-sector employers that engage in interstate business,” Le Monte said. “… Even though it is increasingly common for employers to filter all interviews through a public-relations office, the fact that it is common doesn’t make it legal. It just means lots of higher-ed institutions are breaking the law.”

The process of writing this article illustrated the harms that come with a mandatory intermediary, let alone one that is an administration-aligned Marketing and Communications department. Because the seemingly mandatory intermediary is the subject of this article, following the procedure in this case would have risked hesitation by faculty and staff members to express their unfiltered opinion as they would be sending their response directly to the subject about which they would be speaking. In the beginning stages of researching this story, TSV contacted multiple Scripps faculty and staff members without using MarComm as an intermediary, in explicit violation of their stated procedure, as these emails contained sensitive questions and would require honest responses. TSV’s privacy of communications was lost in the beginning stages of researching this story when an assistant dean cc’d Marketing and Communications on their response, in line with their stated protocol.

While staff members may have little choice but to follow the procedure, adherence by faculty members and on-campus publications seems unlikely. “If a policy says you must contact XYZ office, journalists may do so, but as always they will continue to try to get to primary sources for their stories. That’s their job,” Jones said.

Scripps College’s founder and namesake, Ellen Browning Scripps, was herself a journalist during the 1860s and 1870s and a defender of ethical journalism. Any procedure blocking the direct and open exchange of dialogue on Scripps campus is at odds with the very values that Scripps was founded to uphold, including leadership and integrity, according to the college’s own website. If only Ms. Scripps could see us now.